Iptables explore, implement virtual IP

What is netfilter

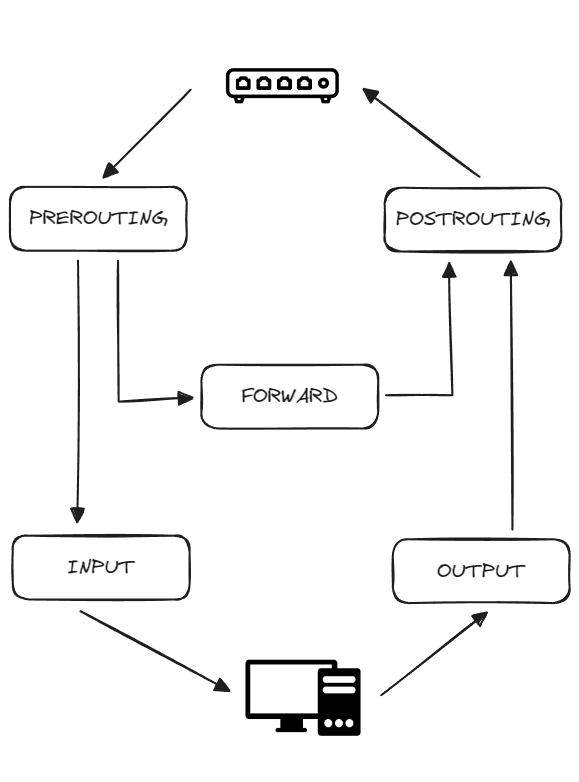

In 1999, the Linux kernel was augmented with netfilter, a robust framework designed to empower users with the capability to tailor network packet processing within kernel space. Netfilter introduces five pivotal hooks distributed at key stages of the network packet’s journey, providing functionality ranging from packet filtering to network address translation. The hooks are as follows:

- PREROUTING

- INPUT

- FORWARD

- OUTPUT

- POSTROUTING

Packets arriving at the host are processed through the PREROUTING -> INPUT sequence, while packets originating from the host follow the OUTPUT -> POSTROUTING path. Conversely, packets that are merely passing through the host, destined for another target, follow the PREROUTING -> FORWARD -> POSTROUTING trajectory.

Netfilter empowers users with the ability to configure rules at each hook, providing granular control over network packet handling within a Linux host. For instance, users can set up a rule at the INPUT hook to filter out packets by dropping them if they originate from a specific IP address, effectively preventing the host from receiving any packets from that source.

You can find more details about at the netfilter official website.

What is iptables

While netfilter provides the foundational framework within the kernel space, iptables is the complementary user-space utility that enables users to establish and manage the rules for each netfilter hook. True to its name, iptables organizes these rules into specific categories known as tables, which represent different types of packet processing functionalities. These tables include:

filter: The default table, which is used to filter the packet.nat: The table that is used to modify the source or destination IP address and port of the packet.mangle: The table that is used to modify the packet header.raw: The table that is used to configure the rules for the connection tracking.

Within each table in iptables, there are several default chains that correspond to the netfilter hooks. For instance, the filter table contains the INPUT, OUTPUT, and FORWARD chains. These predefined chains mirror the packet processing stages managed by the hooks in netfilter. Users can modify the behavior of packet processing by appending or inserting rules into these chains, as demonstrated by the subsequent shell command.

$ iptables -t filter -L

Chain INPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

Chain FORWARD (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

Chain OUTPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

This indicates that, the rules in filter table, which can accept or drop packets, can be applied in the INPUT, OUTPUT, and FORWARD hook. For example, the following command will drop the packet from the IP 1.2.3.4 to the current host:

$ iptables -t filter -A INPUT -s 1.2.3.4 -j DROP

$ iptables -t filter -vnL

Chain INPUT (policy ACCEPT 0 packets, 0 bytes)

pkts bytes target prot opt in out source destination

0 0 DROP all -- * * 1.2.3.4 0.0.0.0/0

Chain FORWARD (policy ACCEPT 0 packets, 0 bytes)

pkts bytes target prot opt in out source destination

Chain OUTPUT (policy ACCEPT 0 packets, 0 bytes)

pkts bytes target prot opt in out source destination

Netfilter hooks are selectively available across different iptables tables because not all hooks are applicable to the functions of each table. For instance, the PREROUTING hook is absent in the filter table, as the filter table is intended to examine packets after a routing decision has been made and is specifically focused on packets destined for the current host.

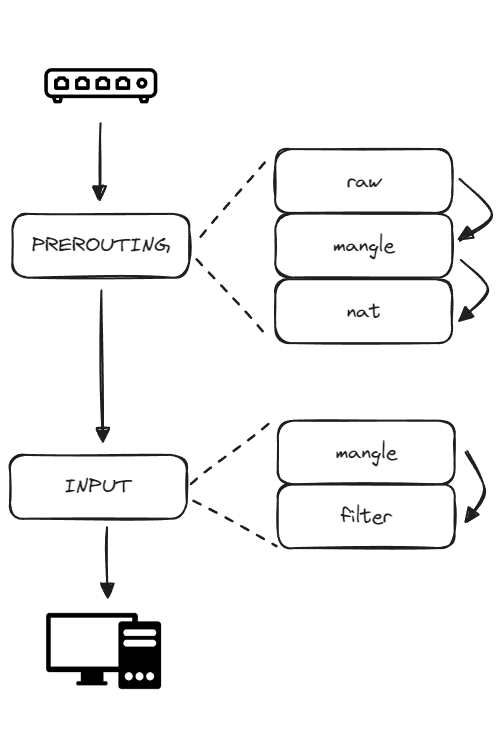

Incoming packets from external sources to the host follow a designated path:

- Hook:

PREROUTING- Table:

raw, chain:PREROUTING - Table:

mangle, chain:PREROUTING - Table:

nat, chain:PREROUTING

- Table:

- Hook:

INPUT- Table:

mangle, chain:INPUT - Table:

filter, chain:INPUT

- Table:

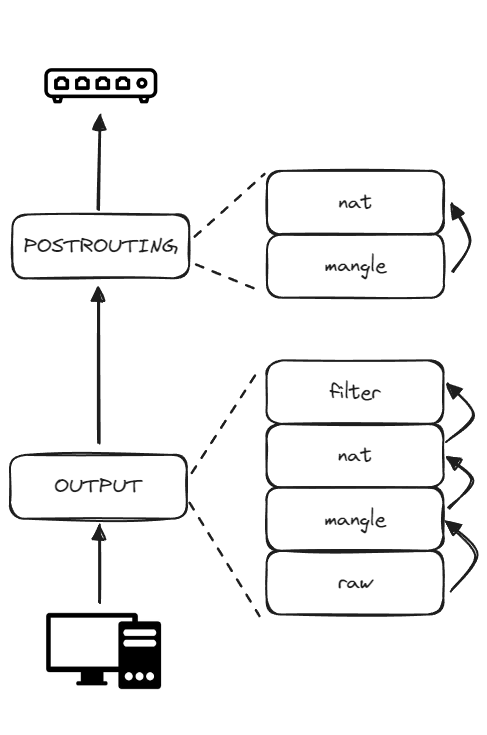

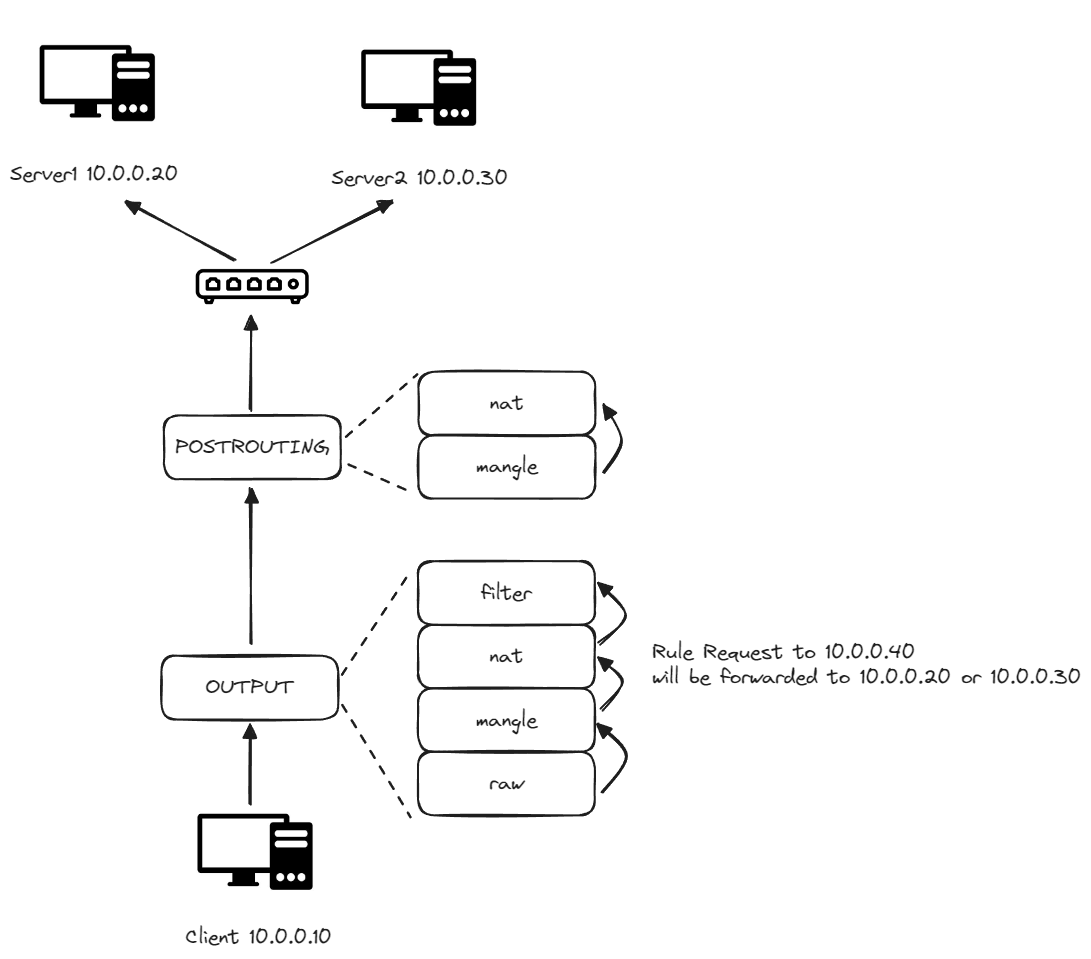

For an outcoming packet from the current host to the outside, the packet will go through the path:

- Hook:

OUTPUT- Table:

raw, chain:OUTPUT - Table:

mangle, chain:OUTPUT - Table:

nat, chain:OUTPUT - Table:

filter, chain:OUTPUT

- Table:

- Hook:

POSTROUTING- Table:

mangle, chain:POSTROUTING - Table:

nat, chain:POSTROUTING

- Table:

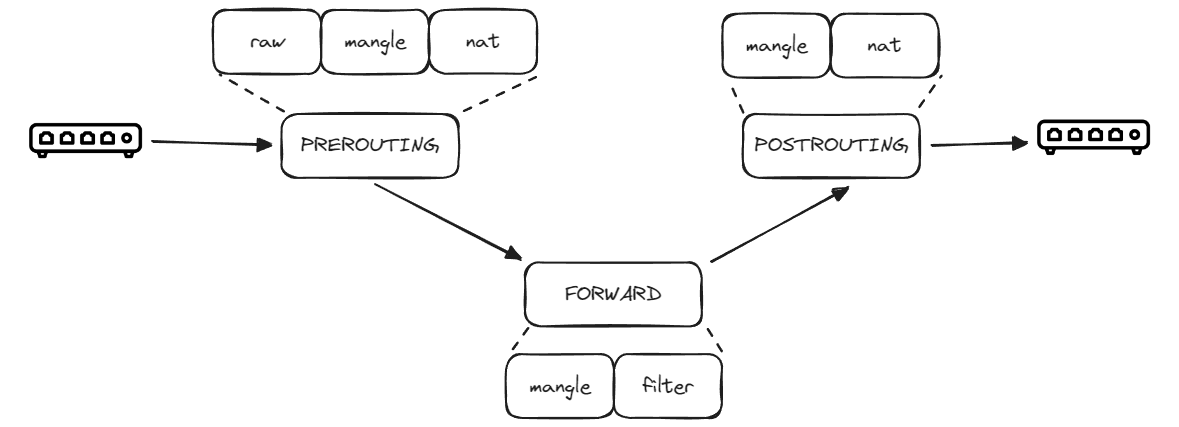

For an incoming packet from the outside, but target to another host, the Linux host can act as a router, to forward the request to that target host, the packet will go through the path:

- Hook:

PREROUTING- Table:

raw, chain:PREROUTING - Table:

mangle, chain:PREROUTING - Table:

nat, chain:PREROUTING

- Table:

- Hook:

FORWARD- Table:

mangle, chain:FORWARD - Table:

filter, chain:FORWARD

- Table:

- Hook:

POSTROUTING- Table:

mangle, chain:POSTROUTING - Table:

nat, chain:POSTROUTING

- Table:

In addition to the default chains, iptables allows users to create custom chains within each table to organize their rules more effectively. However, it’s important to understand that these user-defined chains do not extend the functionality of netfilter; they serve organizational purposes only. For example, it’s not possible to add a rule to the PREROUTING hook within the filter table through a custom chain, nor can additional hooks be introduced into the netfilter.

Demo: Implement virtual IP

As a developer, you might have heard about iptables but never actually used it, leaving it to the realm of DevOps or SREs. However, with the shift towards cloud-native development, understanding tools like Kubernetes — the de facto standard for cloud-native applications — becomes crucial. iptables is one of the mechanisms Kubernetes uses to implement Services.

In Kubernetes, a Service acts as a virtual IP address for accessing a set of pods. This virtual IP doesn’t belong to any individual pod; rather, requests to the virtual IP are distributed among the pods in the Service. In this demonstration, we’ll replicate this functionality using iptables and Docker containers.

We have three containers: client, server1, and server2. From within the client container, we’ll use iptables to set up a rule. This rule will forward requests destined for the virtual IP, 10.0.0.40, to either server1 or server2 at random, mirroring the behavior of a Kubernetes Service.

First, lets create the network and containers.

# Create a network with subnet 10.0.0.0/24

docker network create virtual_ip_demo --subnet=10.0.0.0/24

# Create a client container with IP 10.0.0.1/24

docker run -d --name client --network virtual_ip_demo --ip 10.0.0.10 --hostname client --cap-add NET_ADMIN antrea/toolbox tail -f /dev/null

# Create 2 servers with IP 10.0.0.2/24 and 10.0.0.3/24

docker run -d --name server1 --network virtual_ip_demo --ip 10.0.0.20 --hostname server1 strm/helloworld-http

docker run -d --name server2 --network virtual_ip_demo --ip 10.0.0.30 --hostname server2 strm/helloworld-http

Now, let’s attach into the client container and set up the iptables rule.

# Attach into client container

docker exec -it client sh

# List chains in nat table

iptables -t nat -vnL

The output should be something like

pkts bytes target prot opt in out source destination

0 0 DOCKER_OUTPUT all -- * * 0.0.0.0/0 127.0.0.11

Chain POSTROUTING (policy ACCEPT 0 packets, 0 bytes)

pkts bytes target prot opt in out source destination

0 0 DOCKER_POSTROUTING all -- * * 0.0.0.0/0 127.0.0.11

Chain DOCKER_OUTPUT (1 references)

pkts bytes target prot opt in out source destination

0 0 DNAT tcp -- * * 0.0.0.0/0 127.0.0.11 tcp dpt:53 to:127.0.0.11:38513

0 0 DNAT udp -- * * 0.0.0.0/0 127.0.0.11 udp dpt:53 to:127.0.0.11:40134

Chain DOCKER_POSTROUTING (1 references)

pkts bytes target prot opt in out source destination

0 0 SNAT tcp -- * * 127.0.0.11 0.0.0.0/0 tcp spt:38513 to::53

0 0 SNAT udp -- * * 127.0.0.11 0.0.0.0/0 udp spt:40134 to::53

As you can see, Docker is also utilizing iptables to reroute DNS queries (port 53) to the DNS server it operates on the host. This is part of Docker’s internal management to ensure containerized applications can resolve network addresses efficiently. Docker maintains this setup through custom chains, a best practice that keeps rules organized without directly modifying the built-in tables.

For the sake of simplicity in our demonstration, we’ll bypass the creation of custom chains. Instead, we’ll directly insert DNAT (Destination Network Address Translation) rules. These rules will redirect requests aimed at our virtual IP to either server1 or server2, emulating the load-balancing feature of a Kubernetes Service.

# Redirect packets destined for 10.0.0.40 to 10.0.0.20 with approximately 50% probability

iptables -t nat -A OUTPUT -d 10.0.0.40 -m statistic --mode random --probability 0.5 -j DNAT --to-destination 10.0.0.20

# Redirect packets destined for 10.0.0.40 to 10.0.0.30

# This rule will only be hit if the first rule does not match, approximating the other 50%

iptables -t nat -A OUTPUT -d 10.0.0.40 -j DNAT --to-destination 10.0.0.30

The initial rule we’ve crafted leverages the statistic module to randomly direct traffic to our designated destination IP addresses. With the --probability 0.5 flag, there’s an even chance — specifically, a 50% likelihood — that a given packet will match this rule. Should the packet not match the first rule, it will then be evaluated against the subsequent rule, ensuring it gets redirected to server2.

To confirm the effectiveness of our virtual IP setup, we can continuously send requests to the virtual IP, 10.0.0.40, and observe the distribution of traffic between server1 and server2. This will demonstrate the load-balancing behavior akin to a Kubernetes Service.

# Send request to 10.0.0.40 10 times

for i in $(seq 1 10); do curl 10.0.0.40; done

<html><head><title>HTTP Hello World</title></head><body><h1>Hello from server1</h1></body></html

<html><head><title>HTTP Hello World</title></head><body><h1>Hello from server1</h1></body></html

<html><head><title>HTTP Hello World</title></head><body><h1>Hello from server1</h1></body></html

<html><head><title>HTTP Hello World</title></head><body><h1>Hello from server1</h1></body></html

<html><head><title>HTTP Hello World</title></head><body><h1>Hello from server1</h1></body></html

<html><head><title>HTTP Hello World</title></head><body><h1>Hello from server2</h1></body></html

<html><head><title>HTTP Hello World</title></head><body><h1>Hello from server2</h1></body></html

<html><head><title>HTTP Hello World</title></head><body><h1>Hello from server2</h1></body></html

<html><head><title>HTTP Hello World</title></head><body><h1>Hello from server1</h1></body></html

<html><head><title>HTTP Hello World</title></head><body><h1>Hello from server2</h1></body></html

Exploring Further

The post presents a snapshot of iptables capabilities, especially in setting up a virtual IP. Should your curiosity be piqued and you’re keen to delve deeper into the world of iptables, I highly suggest exploring additional materials to bolster your understanding:

- Dive into the comprehensive documentation and resources available at The netfilter.org project, which is the home for the software behind iptables.

- For a quick reference that you can keep at your fingertips, consider the Linux iptables Pocket Reference by O’Reilly Media.

- To understand the practical application of iptables in orchestrating containerized environments, read through insightful articles like How Kubernetes Services Direct Traffic to Pods, which breaks down the concepts into digestible examples.